Artificial learning under state control: “Mriya” as a platform for dismantling live education

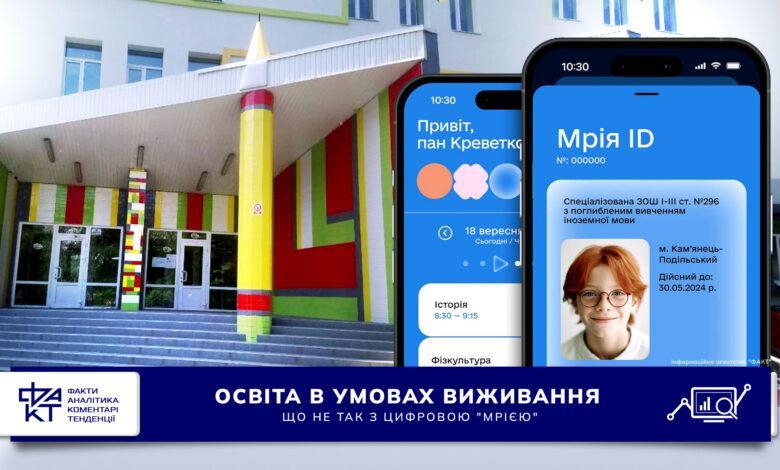

In recent years, Ukrainian education has been living in conditions of constant turbulence: pandemic, full-scale war, evacuations, distance learning, lost contact between school, child and parents. These processes have exacerbated both old and new problems, including unequal access to quality education and emotional burnout among students and teachers. Against this background, the ideas of digitalization of the school system appear to be a logical response to the challenges of the times. In particular, the “Dream” application, which is positioned as a step into the future of Ukrainian education. Its functionality is wide: electronic journals, integration of extracurricular education, elements of artificial intelligence, analytics, automation, feedback for parents. However, despite the bright design and promising rhetoric, the project leaves many questions, first of all, about what kind of education it is trying to build and whether there is a place for a person in this system.

Great educational transition: what is behind the ambitions of “Mria”

Educational application “Dream” officials position it as the new flagship of the digital transformation of the Ukrainian school. We are watching how this project is rapidly moving from the stage of an idea or concept to the phase of full-scale implementation. Last year, it was talked about with caution, as an experiment in several dozen schools. Today, it is presented as a universal educational platform of the state level, which should combine all the key components of the educational process: from grades and diaries to clubs, preschoolers, students and even children studying abroad.

According to the results of the reports for the year of pilot operation, more than two million grades were given through the “Dream” application, and parents entered the system more than 300,000 times to track their children’s educational progress. These numbers are really impressive. According to the predictions of the project authors, in the near future the platform should transform from a school administration tool into a digital educational ecosystem covering all age levels. Already in 2025, it is planned to launch a pilot project for kindergartens, and the next stages will be the connection of vocational and higher education. At the same time, the integration of extracurricular activities: sections, circles, electives will take place.

That is, in the future, “Dream” should become not just a platform for grades and homework, but a digital diary of a child’s development from the moment he first picked up a pencil and until the graduation of a bachelor’s degree. This is an ambitious task that effectively challenges the old structure of educational links, offering instead a unified environment with end-to-end analytics and data management.

Digital diary or digital collar? About the risks of hypercontrol in education

In the context of war and constant anxiety, the platform’s new features seem timely. For example, parents will be able to find out if a child has descended into a shelter during an air raid. Students will be able to report incidents of bullying anonymously. For children who were forced to find themselves abroad, “Dream” will become a bridge to Ukrainian education. All this is positioned as a response to the new reality, which is indeed a very pressing problem now.

However, even these seemingly caring functions raise a number of ethical doubts. Constant monitoring of schoolchildren’s behavior in real time raises concerns about the feasibility of such control. There is a risk that the platform will turn the student into an object of surveillance instead of keeping him a full participant in the learning process. For some reason, the creators of the project ignored these important points.

Another promise that has attracted attention is the use of artificial intelligence. Based on AI, they will create a test generator and a recommendation system that will analyze the learning dynamics of each student and suggest the optimal learning route. It sounds like a scenario from a futuristic series, but within the framework of the “Dream”, as the authors of the project assure, this is a very real prospect. In addition, they promise to introduce gamification and a bonus system. The idea is to make learning more interesting and motivate students through visual achievements, ratings or even material incentives. It can certainly work, but only if the pedagogy is not reduced to clicks, points and virtual badges.

Today, the education system in Ukraine is far from being ready for such a large-scale transformation. The lack of comprehensive training of teachers jeopardizes the effectiveness of the introduction of new tools. Without appropriate training of teachers, technology risks remaining just a technical addition, and not a real means of improving the educational process. In addition, training methods, which for decades were based on unified approaches, are not adapted to the individualization and personalization offered by the “Dream”. The transition from the traditional model to flexible learning trajectories requires significant methodological work, which currently seems to be lacking. In general, these important nuances are overlooked, which can lead to the fact that technological progress is not accompanied by qualitative changes in education.

Tickets, tests, video lessons: all in one application

“Mriya” also integrates electronic documents, such as a student card, which will function according to the principle of digital documents in “Dia”. At the same time, the application plans to make available multimedia educational materials: video lessons, interactive tasks, game modules. Thus, the state bets not only on management, but also on content. If earlier school education depended on a paper textbook, now it depends on the design of a digital platform, a stable Internet, and the availability of gadgets for every child. And here two more problems enter the arena.

One of the weaknesses of the “Dream” project is the approach to filling the platform with educational content. It is assumed that most of the materials will be created and uploaded by the users themselves, i.e. teachers, methodologists, even students and on a free basis. On the one hand, it looks like a democratic approach that encourages the community to participate in the development of the system. But in reality, such a model has many risks. Without adequate payment of authors, the motivation to create high-quality, thoughtful and modern content is significantly reduced. If the work of a teacher or methodologist is not valued in money, the likelihood that the platform will be filled with low-quality, outdated or simply superficial materials quickly increases.

The very willingness of the project to cooperate is illusory. Different platforms can “connect”, but not as full-fledged partners, but as providers of free content. No compensation is provided to the authors, and the selection is carried out non-transparently. The only recorded cases of integration were cooperation with the Kunst and Projector projects, but even here it is only about providing content, and not about a full-fledged technical or business partnership. In fact, companies are offered to give away content just by mentioning their logos on the page. This is not a partnership, but an imitation of openness. In such conditions, it makes no sense either technically or economically to integrate into the platform.

It is even worse that the project does not provide for a clear system of content selection, verification and moderation. The lack of professional curatorial work can lead to the fact that users will receive a chaotic set of materials of different quality and compliance with standards. As a result, “Dream” risks turning from a tool for supporting the educational process into a messy digital library with dubious content.

In addition, instead of investing in live teachers, their qualifications and motivation, the state is once again betting on video lessons. But the experience of the pandemic has already shown that screens cannot replace the classroom, Zoom is not a school, and content does not equal education. However, instead of drawing conclusions, we are repeating the same mistake, only now in the form of a new application. Such a situation calls into question the real effectiveness of the platform and its ability to become a real assistant for the teacher and the student.

We should not ignore the most important problem of the project, which is the inequality of access to the educational materials of the “Dream” platform. The idea of creating a single digital environment sounds attractive, but in reality it risks deepening the divide between different regions and social groups. Not all schools have stable Internet, modern computers or tablets, and many families simply do not have the opportunity to provide children with access to gadgets.

Obviously, such technical inequality automatically excludes a part of students and teachers outside the borders of the “Dream”, turning it into another privilege only for those who live in cities or have the appropriate resources. This creates a situation where the digital transformation of education, instead of bringing closer and providing equal opportunities, actually deepens the existing educational inequality. Without systematic measures to ensure equal access to the platform, all these innovations risk remaining unattainable for a large part of Ukrainian students.

Great digitization: education between reform and monitoring

It is obvious that despite the visual brilliance and modern terminology, a key difficulty remains: without deep meaningful reformation, education risks turning into a platform where only data, not knowledge, will become the main thing. Under the slogans of “national scale” and “breakthrough with artificial intelligence” hides not only an opaque strategy, but also a risky technological hyperintervention in the educational process, which has been balancing between a chronic crisis and endless experiments for years. One should immediately think about whether it is not about creating a new form of state control over education in the digital dimension. Integration at all levels from kindergartens to universities in a country where the basic infrastructure in many schools has not yet been established does not look like reform, but like a vertical of digital surveillance.

Education is increasingly becoming a stream of data, and children are becoming objects of digital monitoring. Stories about 2 million assessments and hundreds of thousands of parents logging into the system against the background of the absence of stable Internet or computer equipment in rural institutions looks like a real mockery or fantasy. Some teachers still work at the level of paper magazines, not because they do not want changes, but because the state does not create any conditions for this. The introduction of such a platform in the face of deep educational inequality creates the image of an elitist digital storefront, which only deepens the gap between schools. Minister of Digital Transformation Mykhailo Fedorov declares about connecting 700 schools. This despite the fact that in Ukraine condition for the 2024/25 academic year, 12,300 institutions of general secondary education (schools, gymnasiums or lyceums) are operating. So these 700 educational institutions are most likely pilot schools with the best technical support. Massive scale-up seems unlikely without billions of investments, which are currently not visible in the budget or plans.

In addition, the project has such large-scale ambitions that it is worth seriously thinking about who actually benefits from it. Millions of children’s data end up in the hands of companies that provide AI solutions, integrate into schools and gradually begin to shape the very essence of the educational process. So, under the guise of a “state platform”, an almost quasi-market of digital education may appear, where the main product will be not knowledge, but information, and instead of the child, the main “client” will be a complex analytical system.

How “Mriya” destroys competition in Ukrainian EdTech

The launch of the educational application “Dream” also influenced healthy competition in the Ukrainian digital education market. Instead of stimulating the industry, the state has created a product that pushes private players out of the market not due to quality or innovation, but due to a monopoly position under the guise of “accessible service for all”.

In less than a year, at least a dozen private platforms that previously worked in the segment of electronic diaries and educational systems, including School Today, Eddy, NIT, lost their positions. Business models built on subscription or paid access to services have been destroyed by the existence of a “free public alternative”. In conditions where every public institution is obliged to optimize costs, the appearance of a platform promoted by the state and which does not require payment automatically pushes commercial decisions to the sidelines.

The situation has developed in such a way that talented Ukrainian EdTech companies, which have invested money, time and expertise in product development for years, are forced to leave the market. Some of them have already moved their offices abroad, opening legal entities in Estonia, Poland, Great Britain or the USA. Their taxes now replenish the budgets of other countries. Formally, only the names of the founders remain Ukrainian. Even the most successful EdTech projects, such as Headway, Grammarly, Promova or Preply, have not been working for the Ukrainian market for a long time. The reason lies not only in access to international capital, but also in the complete lack of incentives for development within the country. While the state publicly calls on business to “be patriotic”, it simultaneously creates such rules of the game that it simply does not make sense to stay in the domestic market. This imbalance creates a deep crisis in Ukrainian EdTech.

Perhaps the most manipulative aspect in this situation is the perceived freedom of choice. Formally, the school has the right to use any service. But there are no real mechanisms for this. First, public school budgets almost never provide for separate costs for digital services. Secondly, there is no legal clarity: the accounting department will not risk paying for an alternative when there is a free “Dream”. Third, the system exerts pressure not by direct bans, but by institutional inertia, because it is quite clear that schools that have already switched to the platform are very likely to never return to other solutions, regardless of the quality of the latter.

So, competition is declared, but impossible. A centralized educational infrastructure is being created, where the entire flow of data, processes and decisions is concentrated in one state system.

Such policies have long-term consequences. When businesses lose incentives to work domestically, not only competition but also innovation disappears. There will be no alternative approaches, experiments, new services. Those who could create a new Ukrainian educational reality will look for a market outside this reality. The paradox also lies in the fact that the “Dream” project, which should become a symbol of a digital breakthrough in education, actually undermines the very possibility of creating a strong educational ecosystem in Ukraine. Instead of developing the market, the state simply supplants it, destroying partnership or healthy competition.

Foreign experience: how the worlds of digital education seek a balance between accessibility and competition

To better understand the prospects of digitization of education, it is worth considering the experience of other countries. After all, the digital transformation of education has long become a reality in the world, and different countries are trying to balance the ambitions of state platforms with market mechanisms and user needs in their own way.

For example, in the US and Western Europe, digital education platforms are usually created and supported by private companies that compete with each other for the attention of schools and parents. There is no single “state system” like the Ukrainian “Dream” here. On the contrary, the variety of products allows educational institutions to choose what best suits their needs and budget, from free solutions with basic functionality to premium platforms with artificial intelligence and gamification.

An example is the Google Classroom platform, which is provided free of charge to schools and often integrates with other Google services. This allows for budget savings, but also increases reliance on a single technology giant, raising data privacy concerns. In parallel, services such as Canvas, Blackboard or Schoology operate on the market, which offer a wider range of functions, but already on a paid basis. This competition drives continuous product improvement and variety of choice, but also creates a challenge: schools with limited resources are often forced to use free or reduced versions.

In Europe, the state more often supports the creation of open platforms with free access or public licenses. For example, in Finland and Estonia, digital solutions for education are often developed in collaboration between the government, educators and IT companies to ensure not only accessibility, but also high quality content. There is a balance here: the platforms are open, but support competition between the various developers of applications and content integrated into the system. This creates an ecosystem where users can choose the best tools for their needs, and developers are motivated to innovate.

However, even in the most developed countries, digitalization of education faces problems. The digital divide, particularly in rural and disadvantaged regions, remains acute. In many cases, the government provides free basic access, but full use of features often depends on own equipment and internet connection. In this context, the Ukrainian project “Dream” can be considered as a rare case of an attempt to centralize the entire educational ecosystem in a single state platform. At the same time, most systems abroad are built on competition, freedom of choice and partnership with the private sector, which supports innovation and a variety of offers. This creates a dynamic market, where education is adapted to the real needs of students and teachers, and not vice versa, to the requirements of a single centralized service.

Therefore, the experience of other countries teaches that digitalization of education is effective only when it combines openness, competition and state support without monopolization and excessive control. Otherwise, the platform risks becoming not an engine of progress, but a digital “collar” that constricts opportunities for development.

As we can see, the “Dream” project has become a kind of demonstrative example of how the state initiative, which should solve the systemic problems of education, in practice creates new ones. Instead of becoming a tool for supporting and developing the educational environment, it risks turning into a monopoly digital showcase without real interaction with participants in the educational process. Formally, everything points to convenience, equal access and innovation. But in fact we have centralization of control, opaque competition and imitation of partnership.

By introducing digital transformation without proper infrastructure, methodical training and openness to business, the state does not modernize the system, but closes it to itself. This repels private initiatives and deprives education itself of flexibility, alternatives and perspectives. And as long as key decisions are made without dialogue with the professional community, “Mriya” will remain not so much a window to the future as a mirror of today’s problems.