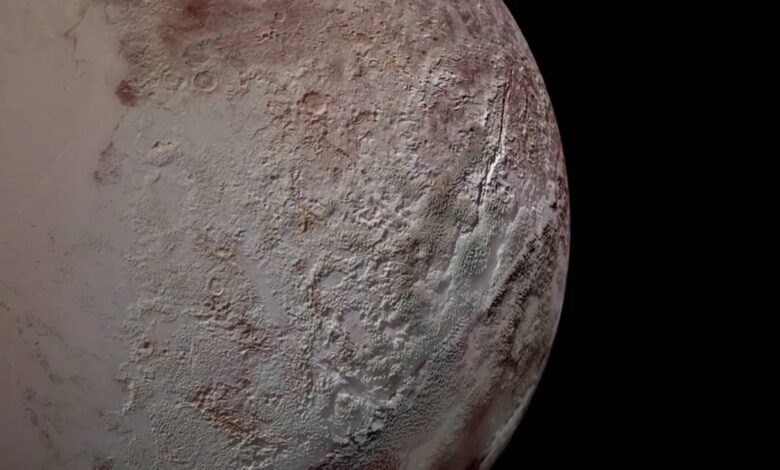

Scientists have discovered 300-meter-high icy “skyscrapers” on Pluto

The New Horizons apparatus recorded spiers of methane ice, each about 300 meters high, on Pluto’s surface. They are located at a distance of up to 7 kilometers from each other and form almost parallel rows. These structures were discovered in mountainous regions near Pluto’s equator, east of the heart-shaped Tombo region. informs Live Science.

Massive formations of methane ice, the size of skyscrapers, may cover about 60% of Pluto’s equatorial zone — more than scientists previously thought. The conclusions are based on an analysis of data collected by the New Horizons spacecraft, which explored Pluto in 2015.

According to scientists, these ice spiers are much larger analogues of the terrestrial penitentes formations, which consist of water ice, are formed in high mountain areas and reach up to 3 meters in height. According to the researchers, methane ice spiers were observed only on the part of Pluto facing the probe, but there are indirect indications that similar structures may cover other areas of the equator that are not available for direct observation.

To detect these formations, scientists have used indirect visual cues — particularly topographic features such as slopes or ridges. Under conditions of equal lighting, surfaces with greater irregularities appear darker because they create more shadows. This means that even if the spiers themselves are not directly visible, they have a noticeable surface darkening effect.

Astronomers analyzed images of Pluto, where light fell at different angles, and studied how the brightness of its surface changed. Attention was focused both on the areas visible to the probe and on the areas that it could not capture directly. Modeling made it possible to assess the influence of the terrain on light reflection. As a result, it turned out that the reverse side of Pluto, saturated with methane, shows a greater unevenness of the topography than the visible side.

Consequently, the study indicates that ice spires extend across a band that covers up to 60% of the dwarf planet’s equatorial zone. Most of these formations are concentrated in the contralateral hemisphere, although it is currently unclear whether they form a continuous structure or are fragmented.